Everything is gold 2020

“The Salon on Agripas Street,” May 2020, Agripas 12 Gallery.

Curators: Rina Peled and Max Epstein

Everything is gold, 2020, Digital print, gold and acrylic paint on canvas, 110×145 cm

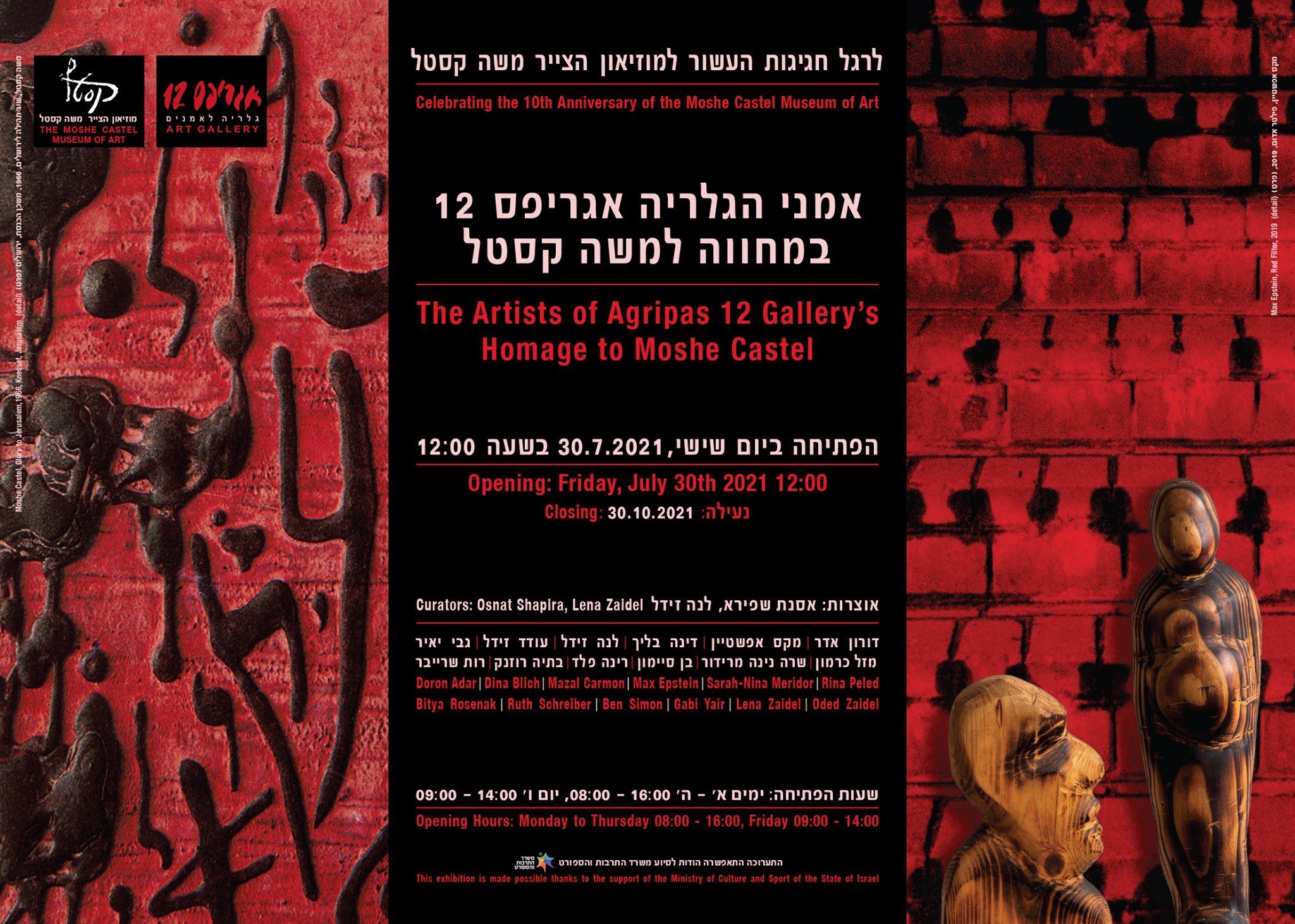

In the group exhibition “The Salon on Agripas Street” (2020), at the Agripas 12 Gallery, the member artists and guests conducted a dialogue with 1900 Vienna in homage to the book Vienna 1900: Blooming on the Edge of an Abyss, Sharon Gordon and Rina Peled (eds.), (Jerusalem: Carmel, 2019).

The book is a kind of retrospective surveying Viennese life at the end of the 19th century. Many of the articles engage in the cultural, artistic and sociological aspects of life in Vienna of the period: architecture, Viennese workshops in which the leading artists of the time were working, such as Gustav Klimt and Josef Hoffmann, Wagner’s music, psychoanalysis, the Vienna coffeehouses, and more. The curators transformed the gallery into a cultural salon in which each of the artists presented a contemporary work corresponding with Vienna at the turn of the century. The works were in various media: painting, sculpture, installation, performance, photography, and jewelrymaking.

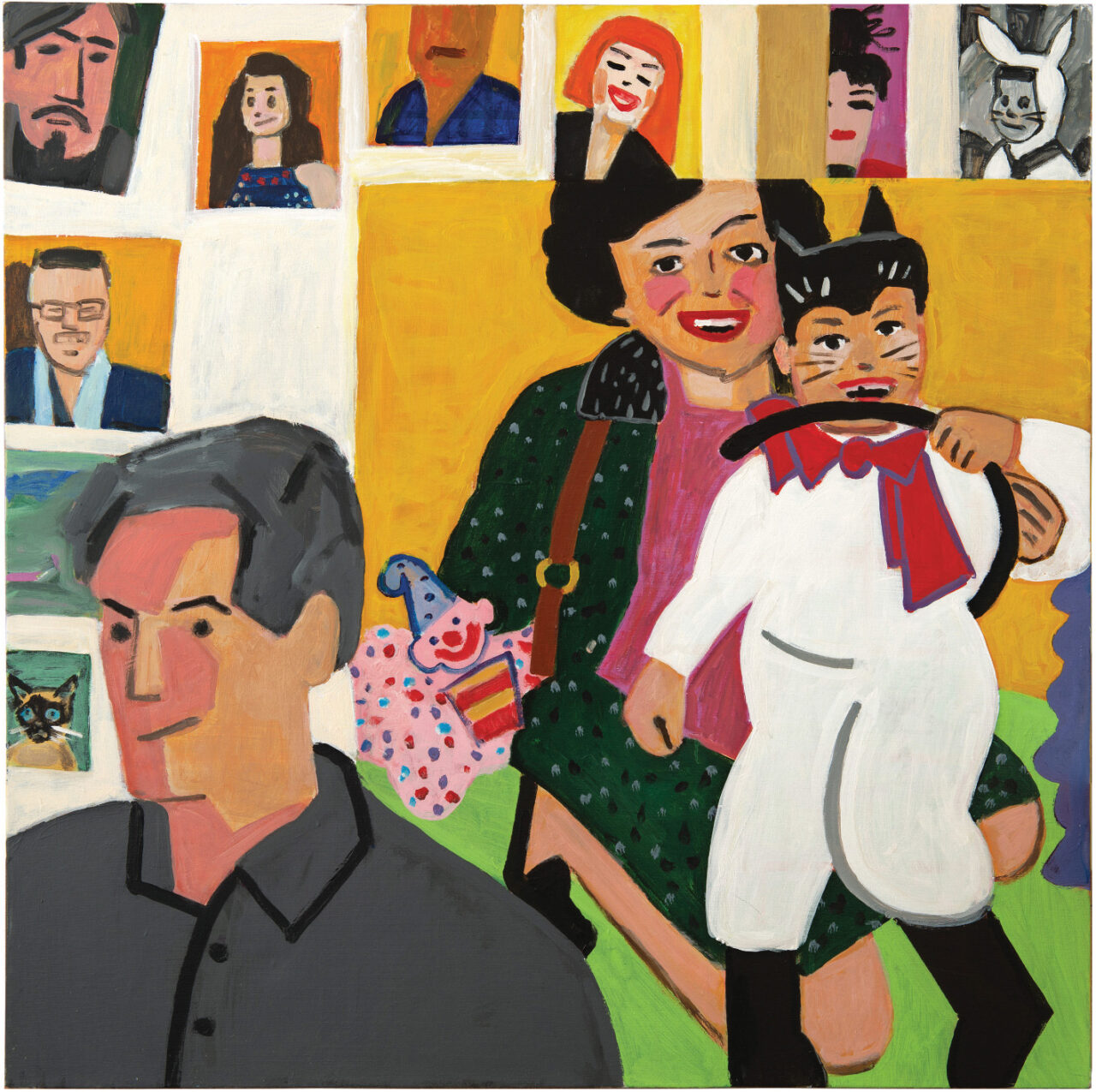

Oded Zaidel proposed a self-portrait for the “Salon Conversation.”

In the same way that Max Kurzweil who painted a portrait of his wife, a work to which Lena refers, Zaidel painted his wife – his usual model – with himself by her side, together with the ladies of Vienna’s high society in the background, as painted by Gustav Klimt, a regular guest at the Vienna salons.

“Spatial Action,” a group exhibition, October 2020, Agripas 12 Gallery and Marie Gallery.

Curator: Nava T. Barazani

The starting point of Oded Zaidel’s painting is an event captured by his gaze while looking at small black and white family photographs from the distant past with some from the recent past. With these raw materials, he continued to other spaces to form a “carnival of colors.” His oeuvre is comprised of layer upon layer of both concrete and metaphorical strata, overflowing the surface like memory and life, creating illusions.

In this painting, a smiling Zaidel is sitting, with a large painting from childhood made after a photograph of a Purim masquerade party in his kindergarten from the 1960s. The painted figures are his mother, and his sister in Puss-in-Boots costume. The childhood painting was already painted by Zaidel and photographed as a painting to paint it again as the major item in the present painting. In the back are additional layers of memory and of time expressed through colorful portraits of artists, including his spouse Lena. Also included is a black and white portrait of the artist as a child in rabbit costume, a detail from the same series photographed in the kindergarten. The old photo albums began to activate the spaces of the artist’s action during the shiva [seven day mourning period] for his father who passed away from Covid-19 a year and a half previously. He told me that with his gaze he sought to examine the unconscious messages such as the photographed subjects’ body language and the selection of the photographs for inclusion in the album. According to Zaidel, the selection represented the way in which one seeks to see oneself. Similarly to the well-considered decisions made in arranging the family albums, he spoke to me about choosing not to create in a melancholy manner despite the timing. “Points in time are festive events that make people happy, as well as the painterly interpretation through the paint and the figures,” Zaidel stated. He rips off the death mask entrapped in the photographs that served as a kind of document of what was and is no more, but at the same time acts like the photographer or the camera, capturing and emphasizing certain details, leaving traces present in the field of memory while erasing others.

From the “True Legends” project curated by Tom Bacon Ohayon

Two of my paintings appear in the second volume, along with works by another 27 artists/illustrators.

The tale I illustrated is called Ziryab Adds a String.

What is culture? Despite all of us using this word all the time, the answer is not simple. Culture is everything that defines and distinguishes one society from another, yet there is something special that can change every person into a cultured person – manners, appreciation for art, and maintaining good relations with the environment. With the help of all of these, every person can be cultured, no matter from which society he hails.

For past centuries, many have praised and lauded European culture. It is indeed worthy of praise – this is the culture that brought us the artworks of the Italian Renaissance and the classical music of Bach and Mozart. From opera to ballet, gourmet restaurants and breathtaking ball gowns, there is definitely cause for praise. But who brought culture to Europe? This tale will respond to this question.

One thousand three hundred years ago, the capital of world culture was the city of Baghdad, in Iraq. Between its splendid walls and twisting streets, the city was proud of its many refined poems and songs, enchanting music, and numerous centers of learning and education. Its many libraries housed wonderful Arabic poetry, science and philosophy books from Greece and Rome, and even ancient religious books from the early culture of Persia and Babylonia. It was there, in the year 789, that Abu Hassan Ali Ibn Nafi was born. Due to his wondrous singing voice, he was called “Ziryab,” or blackbird in Arabic.

Ziryab proved his musical talent at a very young age, playing an instrument and singing. Not much time passed until he was accepted as a student by Ishaq, the royal musician in the court of the great Abbasid Caliph Haroun al-Rashid.

Ishaq taught Ziryab the complicated art of playing the oud, the four-stringed Arabic guitar. The studies were very difficult, as playing the traditional oud involves many scales and complex forms. Ishaq the master insisted that Ziryab learn all of them in the correct way – and only in this way.

Young Ziryab was not afraid of hard work. He practiced for many long hours on his teacher’s scales and rhythms, but something still disturbed him. While playing, he felt new melodies beating in his heart, as if the oud itself were begging to have sounds heard unlike anything else ever sounded.

His strict teacher was unwilling to hear about it – his opinion was that his was the correct way to play the instrument, and that his way was the only way. Ishaq considered any divergence from this way as the insolence of a rebellious student. Ziryab learned that if he wanted to attempt a different kind of playing, he must do so in secret.

Every day, he would go to his teacher, study his craft with the patience of a submissive pupil, and every evening he would secretly leave the city, sit underneath a tree on the bank of the Euphrates, and play strange and unusual melodies.

He enjoyed his experimentation so much that he decided he would go further and break his teacher’s rules entirely: he took his oud, broke it down into its components, and reassembled it – but this time, with five strings instead of four. As if that weren’t enough, Ziryab invented a new style of playing music which integrated delicate instrumentation with marvelous singing. At present, we know many singers who accompany themselves on the guitar, but in those days, it was unheard of, as playing music and singing were separate arts.

One day, the great Caliph asked Master Ishaq which of his students showed the greatest promise. Without hesitation, he spoke of Ziryab as one faithfully devoted to his studies and played properly, exactly as he should. Haroun al-Rashid was intrigued, and asked to have the lad brought to court to play for him. The young Ziryab responded that he would be happy to play before the caliph, but on condition that he be permitted to play on his own instrument. Nothing like that had ever been heard – at the caliph’s court, no one except for the ruler ever set terms.

The caliph’s curiosity overcame his pride, and he agreed to the lad’s terms. How great was the amazement in the hall, when Ziryab presented his unique oud to the audience – an oud with five strings. The courtiers began to whisper among themselves, “Who is this boastful lad who thinks that he can reinvent everything we know and have loved for years?” but all speaking ceased when the young man began to play and sing.

Such sounds had never been heard within the palace. Ziryab’s bold musicianship and marvelous singing were integrated delicately and naturally. It seemed as if Ziryab, assisted by the oud, was playing upon the emotions of those present. He played a joyful song and the audience rejoiced; when he played a sad song, all began to cry. It was if the listeners’ souls, which had become accustomed to the familiar rhythms and scales, suddenly released themselves from their earthly cages to be borne upwards to realms reserved for people privileged to have been exposed to high art. When Ziryab concluded, the caliph and his retinue rushed to praise the wonderful playing and singing, and all were proudly happy to have been in the company of such huge talent.

All were happy except for one: Ishaq the royal musician was infuriated. He was angered by the bold insolence with which the young musician had allowed himself to scorn all of the rules of playing an instrument that he had learned, but more so because he was jealous of his talent. He saw the new admiration that his student had acquired, and feared that Ziryab might replace him as the royal musician. Thus, in thrall to the green-eyed monster – jealousy – he ordered Ziryab to leave Baghdad immediately, warning him that if he dared show his face in town Ishaq would make sure it was his end. The unfortunate Ziryab, who had hoped that his distinguished teacher would be proud of him, was forced to become an exile from his own country.

For many years he moved around, wandering from city to city, alone and destitute. He played in Damascus, Cairo, and Tunisia, learning the unique style of each location. Despite his empty pockets, ZIryab succeeded in finding good people in each place he stopped who admired his talent and paid him for his playing, thus ensuring that he had enough money on which to live.

At the same time, in the city of Cordoba in Andalusia, Spain, the great Caliph al-Hakim I had a big problem. Throughout the entire Arab world, people were talking about the wonderful cultures of Baghdad, Cairo, and Damascus, and no one ever told stories about his city.

He wanted Cordoba to become a world cultural capital, like Baghdad, Cairo, and Damascus. But how does one make a city into a cultural capital? Al-Hakim’s advisors told him that there was a young musician named Zinyab, who moved royal courts with his playing – maybe he could bring culture to Cordoba. The caliph agreed and demanded an immediate royal invitation be issued to Ziryab.

Ziryab, who had his fill of wandering, was pleased, hoping that he would find a new, permanent home in Cordoba. Feeling very happy, he set out on the long journey from Tunis to Morocco, and from there by ship through the Straits of Gibraltar, to Spain. When he reached the gates of Cordoba, he discovered to his amazement that the caliph who invited him had passed away, and was succeeded by his son Abed al-Rahman II, who knew nothing about the invitation to the foreign singer/musician.

The new caliph was wondering about the arrival of the young musician, and when it was explained to him that his father had invited him hoping that he would bring some culture to the city, he decided to honor his father’s memory and invite Ziryab to be the court musician.

When Ziryab entered the caliph’s court, he was shocked and horrified; despite Cordoba being the capital of the great kingdom of Andalusia, the hall was filthy, and the courtiers were sitting around crude wooden tables, shouting at each other and making so much noise, that it was impossible to hear anything except the crowd. Not only was there noise, but Ziryab’s nostrils filled with the sharp scent of sweat and a foul stench.

Every musician who values his art knows that to succeed one must respect every stage on which he is invited to appear. With this realization, Ziryab closed his eyes and began to pluck the strings of the oud, singing a sad, melancholy song that he had composed during his wanderings.

When he finished and opened his eyes, he was astounded to discover that the entire audience was in tears. Not one of those present had ever heard such sweet music. Their crude emotions, which had not yet been refined by high art that refines the soul with its charm, burst out from them in wailing. Ziryab was also very moved; everywhere he went people appreciated his playing, but he had never before seen an audience so totally connected to his music. When the melody ceased and silence reigned over the hall, the young caliph fell on his knees and said a prayer of thanks to his later father’s spirit for the gift that he sent to the court.

To express his thanks, the caliph ordered that a large mansion in the city be given to Ziryab, with a monthly salary of 200 gold dinars. This was a huge sum, which until this point was reserved only for the ruler’s closest advisors. Ziryab understood that from now on he need have no worries about his future.

The grateful musician asked the generous ruler what he wanted in exchange for such a handsome sum. The caliph responded with a single word: “Culture.”

In this way, Ziryab became the first “Minister of Culture” in history. As such, he was charged with the task of transforming Cordoba into a glistening pearl of culture on the world map.

At first Ziryab was happy – not only did his new fortune ensure that he could live his life as he always dreamed of doing, but now his status would enable him to shape his environment and to act to benefit it. After all, every artist dreams of these goals.

Afterwards, when he looked around him, his excitement subsided. Everyone was sitting on a filthy floor. Although there were many different delicacies set on the tables, they tasted bland and were colorless. As if that were not enough, they were thrown onto each table in an unpleasant-looking heap.

Furthermore, those around the table did not look any better than their environment; ZIryab looked on in shock as he saw how each of them took a fistful of food in his hand, shoved it into his mouth, and wiped his hands on his clothing. Everyone was wearing a long, grey, stained robe; each had long hair gathered into a clumsy braid whose thinning edges peeked out from every side. If Ziryab had to bring culture to the city, he was facing a great deal of work.

“O generous ruler,” Ziryab addressed Abd al-Rahman II, “I am grateful from the bottom of my heart for the favor you have bestowed on me. However, please forgive me, but please explain what is the most fitting way in your eyes for me to fulfill the duties of my office?”

The caliph thought about it for some time. He gazed at ZIryab – with his noble modesty, lovely clothing and quiet manners – all the while remembering his wonderful music and beautiful singing, and responded: “Forgive me but I cannot help you with this. I have no doubt that in all matters of culture you are superior to all other citizens of Cordoba. You said that you are grateful and I thank you, but you are a free man, not bound by your thanks, and you are to do anything you wish on condition that you work to enrich our city’s culture.”

Something magical happens when artists are given a free hand. Suddenly, one focus expands to infinite inspired possibilities, and they use their talent to create never-before-seen things.

First, Ziryab established the first school in Europe for music, song, and dance. It was not like the school he knew from his Baghdad childhood: they did not only study the important old laws, but encouraged artists to experiment, innovate, and even invent new styles themselves. The school was a tremendous success, producing many musicians who filled the city with dance, melodies, and song.

Everyone lauded Ziryab for his great contribution to the city and sent him heartfelt thanks, but this was only the beginning of his work. He knew that listening was only one of the human senses, and that if he truly wished to enrich the city’s culture, he would have to enrich the other senses. Only in this way could he develop the greatest art – the art of refining the soul.

He made sure to import the best treasures of the East into the city – fabrics from Palmyra, Mosul and Damascus; books from Baghdad and Cairo; and various spices from India to Marrakech. He replaced the old metal beakers with high-quality crystal goblets and acquainted diners with the use of tablecloths and serviettes.

Because he knew that each facet of life could be rich with art, a new custom began: instead of an overladen table, from now on, there would be courses in an orderly arrangement. He explained that the meal would begin with soup to stimulate the appetite, followed by different salads to accompany fish or meat. The final course would be a sweet dessert or simply nuts and roasted seeds. He even invented several new dishes himself, which were so tasty that even now some restaurants call certain dishes after Ziryab.

After addressing the sense of taste, he continued to the sense of smell, importing spices from all over the world, and even invented a new type of mint toothpaste and the first version we know of for deodorant.

As if that were not enough, Ziryab began to design fashion for the city – people would no longer wear long shapeless grey robs, but from now on would try out various fabrics and designs. Under his patronage, special fashion designs began for each season to have its own style and character: In winter people would wear clothing made of breathable warm material, in summertime in sparkling white robes. Springtime was for boldly colorful fabrics, and dresses embroidered with flowers.

He also demonstrated a new style for men’s haircuts: instead of a clumsy braid above a scraggly beard, he proposed short, well arranged hair, around a clean-shaven face. For women, he invented bangs and encouraged women to experiment with unique haircuts. Thus Ziryab became one of the first fashion designers in history.

Only a short time passed until Cordoba became the world capital of culture and style. Many other cities began to import clothing and cosmetics from Cordoba that were unobtainable elsewhere, as well as artists and craftsmen, chefs and other professionals who could teach how to enrich residents’ lives and refine their taste like the people of Cordoba.

The residents of the city thanked Ziryab and made him their national hero. They asked him about the source of his inspiration for so many inventions. In his modesty and with his manners, he responded, “Me? I just added a string.”

Editor/Curator Tom Bacon Ohayon wrote about the project:

I wanted to tell you a bit about my thoughts behind the tale of Ziryab. I wrote this exactly four years ago (yes, I mean exactly!). At the time, the discussion of Ars poetica was still ongoing, and there was no poet on the newspaper who was not interviewed on his/her absolute position on the issue. When at the time I was working on my book “The City,” my big discovery was that the world was round (“flatlanders” can say whatever they want to), that East and West are not fixed concepts of separate cultures, but the outcome of a series of encounters in which human culture transmitted the baton of enlightenment from nation to nation across the globe.

I do not tend to believe in Divine Providence, especially not when it comes to work, but although my position on this is absolute, as most of my positions, it has accommodation clauses. One such clause refers to the moment of writing. Otherwise I am unable to explain how, during my search for “the first minister of culture in history,” reacting to a certain minister of culture, who exploited identity politics as far as she could for herself, I found the tale of Ziryab – a Persian who moved to Iraq, who wandered from Baghdad to Morocco with his art, until he became the Minister of Culture for Cordoba in Andalusia, Spain. The deeper I researched him the more and more surprises I revealed about him. So many surprises that I didn’t believe it myself: he brought the guitar to Spain! Of course it wasn’t a guitar as we know it but an oud, but from there, versions of the instrument moved through Europe, and the Arabic word ‘oud, or al-‘oud became l’aud and from there to lauta, or lute. But this was only the beginning: he founded the first music school in the west – the Sith school – where the greatest musicians of the 9th and 10th century studied. Among them was the Muslim singer who behaved like a provocative “star,” walking through the streets of Cordoba in a transparent hijab, totally protected by her reputation.

Nor did his work end there: he was also a chef, and the shift from an open table filled with dishes to the European style of movement from course to course, beginning with soup and ending with dessert is attributed to him. It doesn’t sound logical, but then one discovers that there are restaurants all over the world named “Ziryab” (even in Ramallah), and the familiar dish of walnut-stuffed dates is called “Dates à la Ziryab.”

He was the first fashion designer and responsible, among other “firsts,” for inventing the short haircut for me, and even (I’m not kidding) bangs. As if this were not enough, he is also credited with the invention of a new type of mint paste to for a sweet breath, and the first version of deodorant in history.

Now, as the author of True Legends, I have a certain obligation to a small group of my readers not to make such declarations without serious backup. After all, most of these descriptions came from Muslim heritage websites I found online. I then began to research details in European research sites, since the Europeans always want to show that they invented everything, on their own, right? No. It’s hard to believe my shock upon seeing the absolute consensus about the story of this figure. Prof. Joyce Salisbury, one of the biggest experts on the history of medieval Spain, repeated the same story I had read, as did Prof. Eamonn Gearon, scholar of Islam, and Prof. Teofilo Ruiz, who usually loves to shatter the consensus.

Still reeling from the shock of this discovery, I sat myself down to write the tale. One year later, at the launch party of Volume I, this was the story I selected to read aloud to the audience, accompanied by the wonderful Gilad Vaknin on the oud. Gilad, from the Ecoute band, believes as I do that the way to speak about the culture of the East with children is through creating Eastern culture for children. By the way, we loved the music he played for this legend so much that we later used it for the podcast about al-Hassan, the first scientist. Later, when working on the second volume, this was the story chosen to be illustrated by the great painter Oded Zaidel, one of the first on my list of artists for the new volume. He fell in love with the legend and to my great joy, chose to give it color thanks to his huge talent.

Here we are, four years later, and this legend was made into a podcast thus reaching thousands of listeners throughout Israel. I hope you have also listened to it.

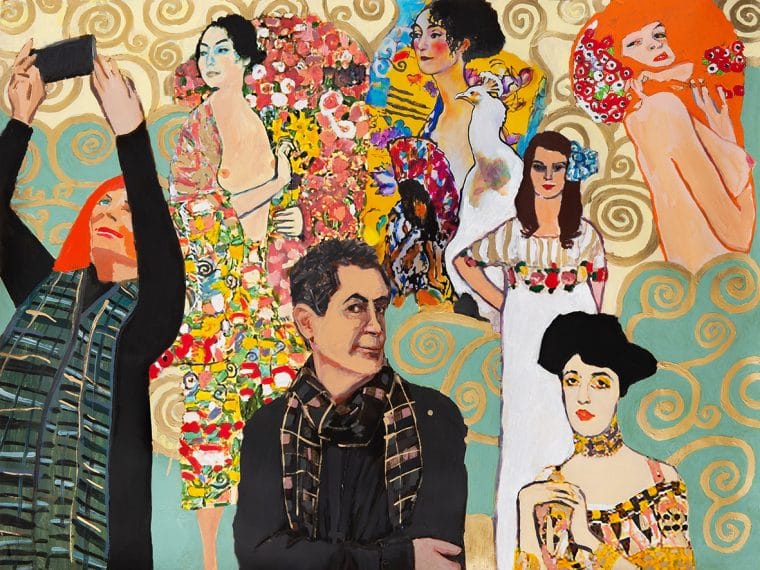

From the gallery text for the exhibition by the artists of the Agripas 12 Gallery in homage to the painter Moshe Castel, 2021, Moshe Castel Museum, Maale Adumim. Curator: Osnat Shapira

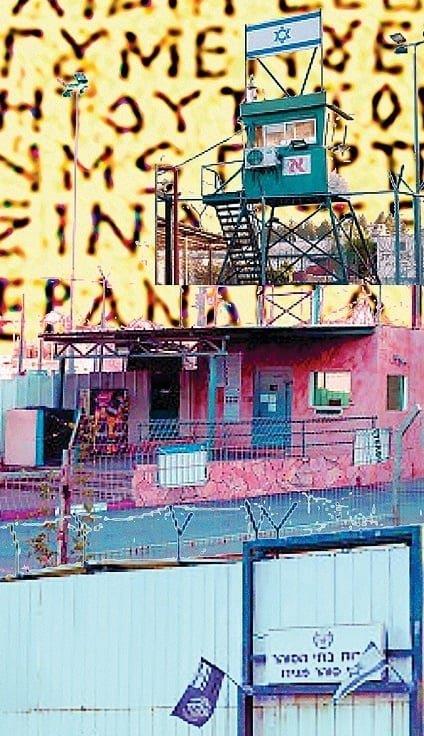

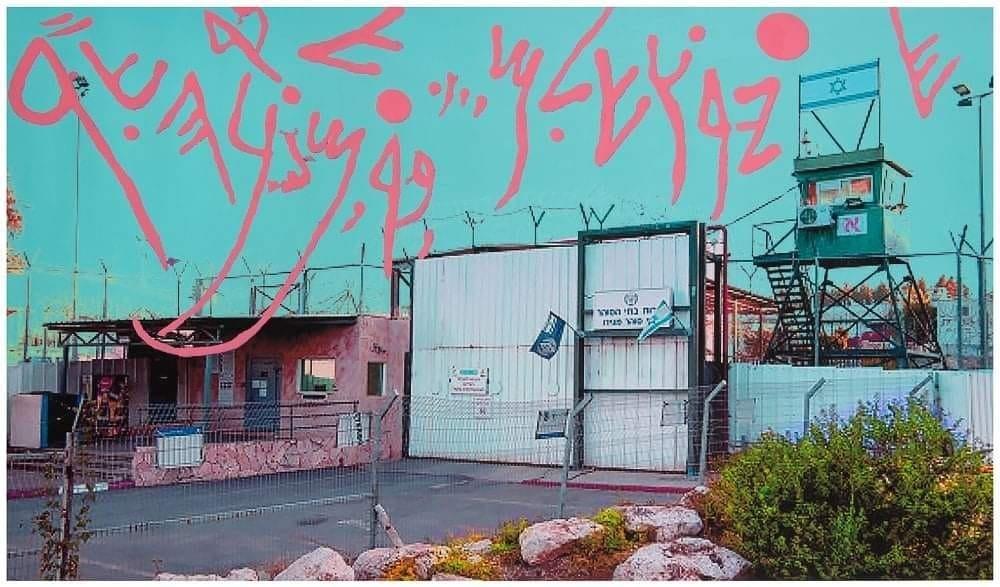

Oded Zaidel’s paintings present the Megiddo Prison for security prisoners, with his own interpretation and additions of emphases through color and form in homage to Castel. Zaidel’s addition, which stands out in the two works, is in the ancient Hebrew letters used in traditional texts, hovering in the sky.

In the first piece, Megiddo Prison, 1 (2019) the dense, yellow handwritten letters stand out from the violet background like neon. The glowing, dense Hebrew letters crowd the skies of the Megiddo Prison that also turned violet. The digital photograph shows the sideways glance towards the guard tower on which the bright blue-and-white Israeli flag is flying, surrounded by the camp’s barbed wire fencing. The sequence of yellow Hebrew letters in the sky is cut off near the guard tower, the letters gently touching it here and there. The letters themselves, which are “hypergraphically” mixed, perhaps tell an entirely different story: ancient, Hebrew, perhaps mystical. The location of the prison on the site of Megiddo connects to the Apocalyptic Christian importance of the site. The choice of the yellow raises various contexts, the most immediate, of course, is the humiliating yellow Jewish Star patch, which also connects to Second Generation author David Grossman’s critical political novel, The Yellow Wind. The violet is reminiscent of a typical characteristic of Moshe Kupferman’s abstract artwork (himself a Holocaust survivor and member of Kibbutz Lohamei Hagetaot. As an artist who focused mainly on abstraction, most of his works are structured on grids with his characteristic scale of greys and violets).

In Megiddo Prison, 2 (2019), the gaze at the prison is from the main gate, slightly to the right of the façade and the driveway. This time, the letters are rosy and isolated, standing out from the background of the azure skies, the overall hues associated with a lyrical, pastoral or saccharine dawn hailing a better future, a feeling of seeming lightness. Ancient Hebrew letters in rose colors decorate the smooth azure skies above a processed photograph of the Megiddo Prison where the numerous Israeli flags flying on Independence Day in the picture intensify the double irony (of it being a prison in general and for political prisoners in particular, especially Palestinian security prisoners). Zaidel creates a sophisticated dialogue with Castel’s late period (his third) – the “Basalt” style – in which Castel integrated photographs and reproductions with his other motifs. But while Castel appropriated his images in a rooted, Zionist approach, Zaidel’s dialogue is critical and political. The Israeli flag stands out in both paintings in the series, sharpening the political aspects of Moshe Castel’s oeuvre, while the location he chose in the Museum expands Zaidel’s lexicon in a work not as typical for him. Tel Megiddo is a pilgrimage site for Christians who believe it is the site of Jesus’s Second Coming and that it is where Armageddon will take place – the beginning of the Apocalypse.

As a reserves soldier, Oded Zaidel spent many long hours in the guard tower at the Megiddo Prison, which evidently inspired these artworks.